Too much heat and too little moisture the past few years have left many pastures and hayfields nutritionally deficient in some regions of the U.S. As cow/calf operators and veterinarians look to address cattle nutritional needs moving forward, Jeffery Hall, DVM, PhD, DABVT, offers a reminder to evaluate essential trace minerals in the process.

While trace mineral deficiencies can vary widely by animal and region, the most common ones Hall sees in cow herds today are insufficient copper, manganese, selenium and zinc. (More information on these below.)

“All of these typically have an impact on immune system function, reproductive function and growth, and they’re all critical for financial stability in calf/calf operations,” says Hall, cattle technical services veterinarian with Huvepharma, Inc., and former Utah State University professor in the Department of Animal, Dairy and Veterinary Sciences.

The Most Common Deficiency

Insufficient copper is the most common deficiency he sees in cow/calf operations. More than 60% of beef cattle have that deficiency, he estimates, based on the more than 6,000 liver samples he evaluated annually while at the university.

“On average, you’re looking at basically two out of every three cows you see driving down the road likely have a copper deficiency,” he says.

Selenium deficiency is almost as common as copper deficiencies in some regions of the United States, making it the second-most common trace mineral deficiency Hall sees. This deficiency varies largely based on soil content levels. The U.S. Geological Survey provides a county-by-county report on selenium levels in the soil, which can be useful in the initial determination. (Click here to view that information.)

Manganese and zinc deficiencies, while less common, are still significant in cow herds across the country.

Hall estimates between 4% and 6% of liver samples he’s tested indicated a zinc deficiency, unless an environmental stress such as drought was present. Drought often exacerbates the degree of deficiency of some trace minerals, including zinc.

“In areas of drought, sometimes the percentages of zinc deficiency would be up around 12% or 13% of samples tested,” he says.

Mama Cows Deplete Their Nutrients For Calves

Hall advises supplementing cows orally with trace minerals year-round to meet their nutritional needs and to ensure calves are born with adequate reserves.

“Over 90% of the mineral transfer occurs in that last trimester of gestation. That’s critical because in the first three months of life over 95% of that calf’s diet is milk and there’s very little of some of these trace minerals in milk,” Hall says. “Yet, during the first three-month period of life, the calf should at least triple its birth weight, so it has to be born with higher body reserves of minerals in the liver.”

In the process of the cow providing adequate nutrition to her calf, she often depletes her own system of key trace minerals in the process of ensuring the calf is born with adequate levels.

“So that period from calving to rebreeding is also critical to build the cow’s system back up to where you get good reproductive performance within your cow herd,” Hall says.

Even after cows breed back, they usually still have calves at their side. “So supplementing the herd during that growth phase of the calf is also critical to make sure you get optimum production out of your calf growth,” Hall says. “When you start adding these different time periods together, you’re better off just supplementing year-round,” he adds.

There Is Significant ROI Available

Too often, producers focus only on the costs associated with providing nutrient supplementation and don’t understand the financial benefits they’ll gain. Hall says veterinarians can often change their perspective by explaining the benefits in economic terms.

He says culling open heifers is the biggest financial loss most ranches and farms incur, and the problem often could have been corrected by addressing those animals’ nutrient needs. He estimates a culled first-calf heifer costs the ranch between $500 and $700 on average (in 2023 dollars), because of the investment in feed, vaccinations, dewormers, and time the producer invested in her for nearly two years.

“If you have to cull her after her second calf, you’re still losing about $250 (in 2023 dollars) in overall ranch profit on that cow, so those young open cows are a big financial loss to ranches,” Hall says. “A lot of ranchers don’t really understand that until it’s explained to them in detail.”

The opposite is true, too. Those calves and cows that have improved immune system function end up with less disease which results in fewer veterinary care costs. That means more live calves at the end of the year to sell, which puts more money in the rancher’s pocket.

“When minor nutritional deficiencies are corrected, it’s not uncommon for me to see a 30- to 35-pound increase in weaning weights across all animal averages in the herd,” Hall says.

He adds that with severe deficiencies, it’s not uncommon for him to see an increase of 70-plus pounds in weaning weights. He has worked with some producers whose cattle had such severe nutritional deficiencies they were culling 15% of their cow herd annually, because the animals were found open at pregnancy checks and/or weaning weights were off..

“Once we got that corrected, we got those cows up into the mid- 90% on the breed-back efficiency, and their calf weaning weights went up by 65 pounds per calf or more,” he says. “You can pay for a lot of really good mineral and a lot of testing with that type of a change in your overall final output.”

Some Liver Biopsies Can Help

Hall advises producers and veterinarians to do some testing to find out where a herd is at nutritionally as they supplement. “Then adjust the program accordingly to make sure that you’re optimizing your overall performance within the herd,” he says.

Conducting liver biopsies is one of the best mechanisms for determining trace mineral deficiencies in the herd, particularly for copper and selenium levels, he says. A secondary step is to then do nutrient and ration analysis to determine the cause of a deficiency.

Hall is a proponent of testing several individual animals, though the cost of testing too many animals is unrealistic. In herds where every animal is on the same pasture and identical supplements, he still recommends pulling 10 to 12 liver samples for evaluation.

Hall says doing liver biopsies during general herd evaluations in the fall is one of the best times to conduct evaluations. At that point, producers are weaning calves and veterinarians are doing pregnancy checks, so the animals are already being run through a chute.

“The other thing about doing a liver biopsy at pregnancy check is if you identify a deficiency that then gives you a window of time to fix it before that next generation of calves hit the ground,” Hall says.

If the veterinarian and producer are looking to identify causation for a specific problem, then testing at the time that the problem would have been initiated is important.

A third option is to do liver sampling on cull cows when they go to the processing facility. “That can work as long as the animal goes straight from the pasture to the processor and the producer doesn’t decide to fatten her up a little before she goes,” Hall says.

Along with doing herd and individual animal evaluations, producers can also consider having pastures, hay and other feedstuffs tested for the minerals and levels present. Oklahoma State University, for one, offers mineral composition analytical services. In 2022, the fee was $12 per sample to get macro and micro minerals levels assessed.

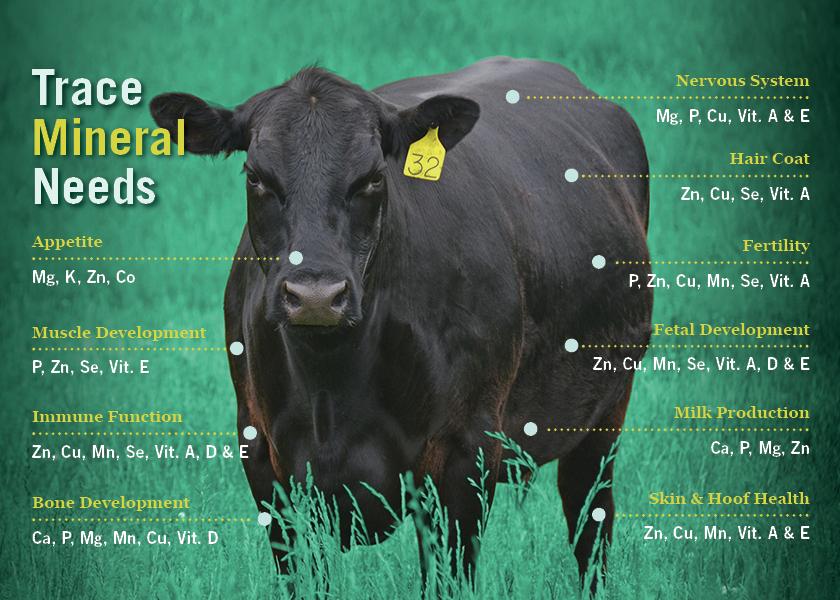

What Key Trace Minerals Provide To Cattle

Hall notes some of the key functions that copper, manganese, selenium and zinc support good cow/calf herd health include:

1. Copper – It supports a number of different enzyme systems in the body associated with energy metabolism, immune function, antioxidant defense systems, connective tissue development, growth and maturation, reproduction and iron metabolism.

2. Manganese – It plays an important role in enzyme systems associated with growth, bone and joint development, reproduction and antioxidant defense systems.

3. Selenium – It supports antioxidant enzymes such as glutathione peroxidase, iodine metabolism, immune function, reproductive function, and is critical for good enzyme function.

4. Zinc – It is important for proper metabolism, growth, gene regulation, reproduction, immune system function and skin health.

What Works Best?

Oral trace mineral supplementation is a good fit for most cow herds. However, several trace mineral supplement formulations with different administration routes are available for use, write Drs. João Bittar and Roberto Palomares, respectively, in their article A Research-Based Summary on Trace Minerals for Cattle.

Some of the factors they recommend considering include: the initial mineral status of the herd (normal levels or borderline to severe deficiencies), duration of supplementation required, the bioavailability of mineral components, ease of administration (injectable, bolus or capsule, salt block or feed), and whether the formulation will be a single or multiple mineral supplementation.

Dr. Palomares, a professor at the University of Georgia College of Veterinary Medicine, says producers sometimes face challenges supplementing trace minerals because of variability in the product or difficulty in assessing intake levels. He addressed where and when injectable supplements have a fit in a recent Have You Herd podcast.

SOURCE: Drovers By Rhonda Brooks

PHOTO: Lindsey Pound