Weather is one of the most important factors affecting producers’ selection of calving season. This is closely linked to forage and feed availability. This undoubtedly creates a regional pattern in calving season across the nation.

Research has shown that calves born into fall-calving herds are typically born lighter. This is in part due to the high summer temperatures altering blood flow patterns. This occurs during the three months prior to calving when the most fetal growth takes place. Likewise, calves born in the spring – especially following a hard winter – will likely be heavier. A long-term study from the University of Nebraska showed that for every 1ºF decrease in average winter temperatures, you can expect in an increase in 1 pound of birthweight and an increase of 2.6% in calving difficulties.

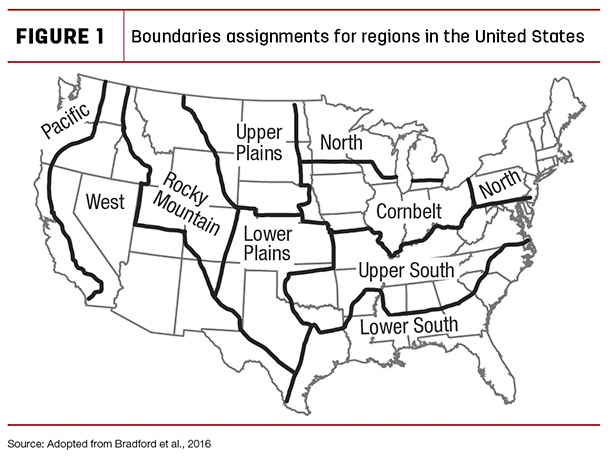

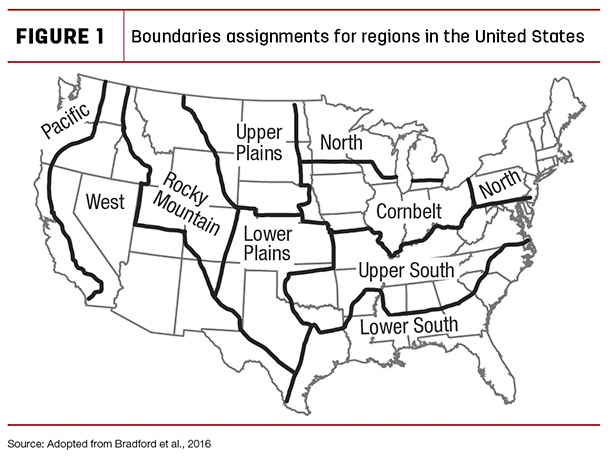

So, the question remains, can lighter-birthweight, fall-born calves catch up and compete with similar weaning and yearling weights? A 2016 study published by the University of Georgia looked at the impact of calving season by region on growth (weaning and yearling weight) in Angus herds. The U.S. was divided up into nine regions based on climate and topography related to cow-calf production (Figure 1).

Data from the American Angus Association was then used to determine the impacts of the calving season (spring versus fall) and region on growth and production traits. The aim of this study was to look at calving season on a comprehensive, national scale. By using purebred Angus cattle, the genetic playing field could be somewhat level and allow data to focus solely on calving season by region. However, one must keep in mind, genetic differences, such as the inclusion of Bos indicus, which is often used in hot humid regions as a management tool.

The largest portion of Angus cattle were in the Cornbelt, Lower Plains, Rocky Mountains, Upper Plains and Upper South regions. Nearly 90% of these calves were born in a spring calving system (February and March) in these regions.

After analyzing calf performance data from over 45,000 head of calves from 1,482 herds, it was found that fall-born calves were heavier than spring-born calves in the South regionals, where fall is the primary calving season. In the Upper South, there were no seasonal differences in weaning weight or yearling weight between spring- or fall-born calves, despite differences in environmental conditions. Spring-born calves tend to be heavier than fall-born in the North and Upper Plains.

There were no differences in weaning weight and yearling weight between calving season in the Upper South nor in the Lower Plains. However, fall-born calves in the lower southern region were constantly heavier at weaning and as yearlings. Fall calving was most advantageous for producers in hot and humid climates, such as the Southeast.

With feed being one of the top production costs, matching the nutritional requirements of the herd with feed and forage availability is likely is driving factor in calving season selection. In addition, environmental and management factors were significantly contributing to differences in weaning and yearling weight, highlighting the importance of the environment for cattle production. Overall, spring calving seems to be king in the colder north and western regions and in the hot humid southern states. Fall calving yields equally beneficial production conditions, overcoming lower birthweights with competitive weaning and yearling weights.

Source: Kalyn Waters for Progressive Cattle Published on 17 September 2021

Weather is one of the most important factors affecting producers’ selection of calving season. This is closely linked to forage and feed availability. This undoubtedly creates a regional pattern in calving season across the nation.

Research has shown that calves born into fall-calving herds are typically born lighter. This is in part due to the high summer temperatures altering blood flow patterns. This occurs during the three months prior to calving when the most fetal growth takes place. Likewise, calves born in the spring – especially following a hard winter – will likely be heavier. A long-term study from the University of Nebraska showed that for every 1ºF decrease in average winter temperatures, you can expect in an increase in 1 pound of birthweight and an increase of 2.6% in calving difficulties.

So, the question remains, can lighter-birthweight, fall-born calves catch up and compete with similar weaning and yearling weights? A 2016 study published by the University of Georgia looked at the impact of calving season by region on growth (weaning and yearling weight) in Angus herds. The U.S. was divided up into nine regions based on climate and topography related to cow-calf production (Figure 1).

Data from the American Angus Association was then used to determine the impacts of the calving season (spring versus fall) and region on growth and production traits. The aim of this study was to look at calving season on a comprehensive, national scale. By using purebred Angus cattle, the genetic playing field could be somewhat level and allow data to focus solely on calving season by region. However, one must keep in mind, genetic differences, such as the inclusion of Bos indicus, which is often used in hot humid regions as a management tool.

The largest portion of Angus cattle were in the Cornbelt, Lower Plains, Rocky Mountains, Upper Plains and Upper South regions. Nearly 90% of these calves were born in a spring calving system (February and March) in these regions.

After analyzing calf performance data from over 45,000 head of calves from 1,482 herds, it was found that fall-born calves were heavier than spring-born calves in the South regionals, where fall is the primary calving season. In the Upper South, there were no seasonal differences in weaning weight or yearling weight between spring- or fall-born calves, despite differences in environmental conditions. Spring-born calves tend to be heavier than fall-born in the North and Upper Plains.

There were no differences in weaning weight and yearling weight between calving season in the Upper South nor in the Lower Plains. However, fall-born calves in the lower southern region were constantly heavier at weaning and as yearlings. Fall calving was most advantageous for producers in hot and humid climates, such as the Southeast.

With feed being one of the top production costs, matching the nutritional requirements of the herd with feed and forage availability is likely is driving factor in calving season selection. In addition, environmental and management factors were significantly contributing to differences in weaning and yearling weight, highlighting the importance of the environment for cattle production. Overall, spring calving seems to be king in the colder north and western regions and in the hot humid southern states. Fall calving yields equally beneficial production conditions, overcoming lower birthweights with competitive weaning and yearling weights.