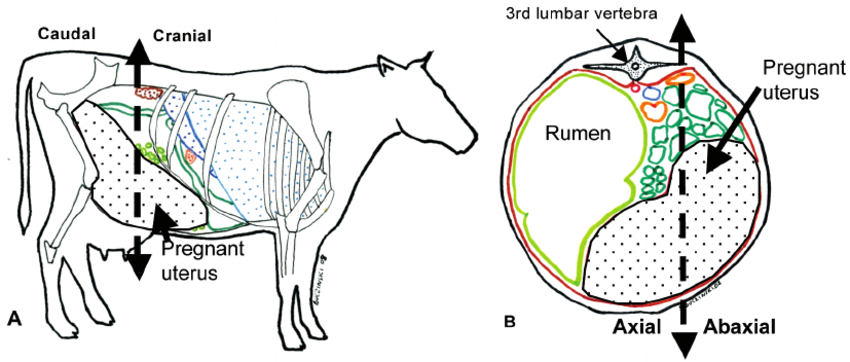

Above Photo: Anatomic topography of the gravid uterus in bovine late pregnancy (right lateral and transversal views).

ResearchGate.net

A client calls up and says he needs help — one of his best cows just calved and has “lady parts” hanging out her back end. Before you decide your next step, ask the client some questions to gain a better sense of what you need to do next, advises Dr. Keelan Lewis, owner of Salt Creek Veterinary Hospital, Olney, Texas.

“Ask if it’s the size of a cantaloupe, a basketball or a feed sack,” Lewis says. “If they say a cantaloupe or basketball, you might say put her in a pen, and I’ll get to her as soon as I can. If they say a feed sack, it’s likely a uterine prolapse, and you need to pack your GoBox.”

A uterine prolapse is a true medical emergency requiring quick intervention, adds Dr. Meredyth Jones, associate professor, Oklahoma State University and Large Animal Consulting and Education.

“It’s about the worst thing that can happen to a cow,” Jones says.

A prolonged delivery, a large calf, and even low blood calcium levels can contribute to a uterine prolapse, Jones says. Most occur immediately after birth and nearly always within 24 hours of delivery.

“When I was in practice, we actually had a chart taped to the wall by every single phone in the clinic,” she recalls. “That way, no matter who answered the phone, they could help the client determine the type of prolapse, because it’s so important.”

Following are some common tools and tips, along with a handful of do’s and don’ts, four practitioners shared with Bovine Veterinarian recently that they hope will help you and other practitioners, especially recent graduates, the next time you face this medical emergency.

KEEP HER ON THE FARM.

Unless the client is already halfway to the clinic, tell them to keep the cow calm and contained on the farm, says Dr. Lainie Kringen-Scholtz.

If the animal is on pasture, the client needs to either walk her slowly to a pen or figure out how to confine her to a smaller area in the field. Some producers use ropes or fence panels to create a small, temporary pen.

“The whole goal is to keep the cow from moving too much and snapping the uterine artery, hemorrhaging and dying. Those arteries are fragile, so it’s a real risk,” says Kringen-Scholtz, associate veterinarian at Twin Lakes Animal Clinic, Madison, S.D.

One caution, Jones adds, is to instruct the client to not put the animal in a head gate. “If she’s standing but weak you run the risk of her going down and choking,” she explains.

CONSIDER WHAT ‘TOOLS’ YOU MIGHT NEED ON-SITE.

A cow uterus weighs well over 50 lb., Kringen-Scholtz says, so either take an extra person or two along with you to help, or make sure the client is available to lend a hand once you’re on the farm.

As you head out, throw some beach towels and a box of large, heavy-duty garbage bags in your truck. Lewis uses the latter much like a washing machine. She envelops the uterus in the bag and then washes the uterus with warm water and a mild disinfectant. The bag also protects the uterus from potential contaminants.

Jones likes to use a garbage bag when the animal is recumbent on the ground in a “frog-legged” position. Once the cow is in place, Jones kneels behind the animal and lifts the uterus off the ground, while a helper slides one end of the bag under the uterus and over the top of the cow’s back legs.

If the animal is standing, Jones prefers to use a beach towel as a sling. “A towel won’t stretch as much from holding the weight as a garbage bag,” she explains.

Two people, one on each side of the cow, can hold the uterus off the ground with the towel while Jones works. “That allows me to focus on cleaning the uterus and pushing it back in, and it makes the process less tiring,” she says. “It’s really difficult to have to both pick up the uterus and simultaneously push it back in.”

Some veterinarians will pour sugar over the uterus to keep the tissues supple and reduce swelling, prior to trying to replace it. “Sugar removes water from the tissues, making it easier to push the uterus back into the pelvic canal,” says Dr. Shawn Clark, Redmond Veterinary Clinic, Redmond, Ore.

Jones advises against using oxytocin to try and shrink the uterus. “Oxytocin will turn the uterus into a brick and you won’t be able to replace it,” she says. “You want the uterus to stay big, floppy and pliable, so you can work with it.”

HANDLE WITH CARE.

Jones begins replacing the uterus by kneading and pushing it with the palm of her hand, starting at the cervical end nearest the vulva. Even with care, damage often occurs.

“Try not to use your fingertips, as they can punch through the uterine wall, but sometimes it is unavoidable,” she explains. “Some caruncles are likely to come off in your hand as you’re pushing,” Jones adds. “That can be really distressing, but don’t panic. You do the very best you can and realize that this is a tough situation, and there are a million things that can make a uterine prolapse go bad.”

Kringen-Scholtz agrees fixing a uterine prolapse is often a challenge, even for seasoned practitioners to correct.

“If the animal has anything hanging out after the cleaning, we consider that a uterine prolapse and an emergency, no matter how much is hanging out,” she says, adding that sometimes you will lose the animal.

“I remember how hard that was as a young graduate, but you have to learn how to let it go and move forward,” she says.

YOU CAN DO THIS.

Once you have replaced the uterus, you need to make sure both horns are completely extended so a prolapse doesn’t reoccur, Jones says.

“Checking the uterine horns is relatively easy to do if you are tall and have long arms,” she says. “If not, you can use a pop bottle or wine bottle as an arm extension. What I do is stretch my arm and flap my hand up and down to see if I can shake that end loose,” she adds.

At this point you can decide if you’re going to lavage the uterus. Jones says she does not and considers it a personal choice.

Likewise, Jones says veterinarians have different opinions on whether to use a vulvar stitch. She favors using one.

“The only thing worse than putting a uterus in once is putting it in twice,” she says.

Jones administers oxytocin at this point to get the uterus to clamp down, which minimizes the chance of a prolapse reoccurring. Kringen-Scholtz’s adds her standard approach is to provide an antibiotic and prescribe a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory, such as flunixin or meloxicam.

ADDITIONAL CONSIDERATIONS.

The treatment of a uterine prolapse is understandably not always a straightforward undertaking, Jones says.

“Replacing the uterus into its proper position is more difficult than a vaginal prolapse,” she says. “If a uterine prolapse is severe enough, the option of amputation is sometimes best. This option gives the cow time to raise her calf, but she would need to be culled due to her lack of a reproductive tract.”

However, if you are able to replace the uterus and the cow survives in good condition, Jones says she wouldn’t automatically recommend the client cull the animal.

Kringen-Scholtz often does recommend culling. “It’s hard to know how much scarring is present,” she explains. “If the animal is really valuable, putting her in an embryo transfer program is another option to consider.”

Source: Bovine Verterinarian, By Rhonda Brooks November 1, 2021