Of all the factors out of the control of livestock producers, weather is probably the most unpredictable. Yearly and seasonal differences in precipitation can have large impacts on forage production and operation profitability. Developing strategies to help minimize the impact of drought and capitalize on forage abundances in wet years can help livestock producers minimize risks associated with weather volatility.

Adaptive management is a strategy that livestock producers can use to help manage some of the year-to-year variability in forage production, and it can be incorporated into drought decision making processes. Adaptive strategies often focus on increasing flexibility within an operation and actively monitoring conditions to influence decision making. At its core, adaptive management is a systematic approach to grazing management that involves constantly monitoring outcomes of management decisions and accommodating change to improve rangeland health and operation profitability. Below are some examples of adaptive management strategies.

Climate Planning Tools

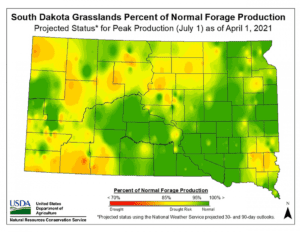

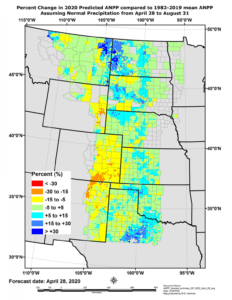

Another tool developed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) is GrassCast (Figure 2), which releases annual predictions of grassland productivity at the county level based on historic 40-year forage and climate data. This tool can be used to give producers an estimate of how much forage above or below normal they can expect under wet, dry and normal precipitation scenarios.

While none of these tools are 100% accurate (again, there’s no crystal ball), they can help producers plan for forage deficiencies to reduce risk and increase their operations’ resiliency.

Stocking Rates

Drought and production forecasting tools can be used to help set stocking rates to match forage resources to forage demand. In an ideal world, everyone would have long-term records of stocking rates and forage production to estimate average production and adjust from there. Rangeland productivity tools from the NRCS Web Soil Survey can give producers an estimate of average forage production for pastures; combined with forage outlook scenarios (e.g., ± 30% of normal), producers can estimate appropriate stocking rates for the year using the SDSU Extension Grazing Calculator.

Grass banking is another adaptive management strategy that involves setting conservative stocking rates based on dry year (below-normal moisture) production levels for all pastures. This allows producers to ‘bank’ forage resources in the event of a drought, reducing the chances of pastures becoming overgrazed. At the same time, this allows for heavier stocking in favorable years to increase animal production. Overall, these strategies can reduce the need to sell cows during unfavorable markets and improve profitability during above-normal precipitation years.

Herd Flexibility

Another strategy for incorporating adaptive management into your operation is maintaining herd flexibility in the proportion of cow-calf pairs to yearling cattle. In the case of a drought, yearling cattle can be sold early in the season to allow for more grass for cows to eat. Selling yearlings also won’t have a negative impact on established herd genetics, and they are more easily restocked if drought conditions improve. In high forage production years, keeping yearlings or custom grazing yearlings can allow producers to capitalize on excessive grass, increasing animal production on the operation. As with any adaptive management plan, having an established protocol for when and which animals to sell in drought can help producers mitigate risk.

Conclusion

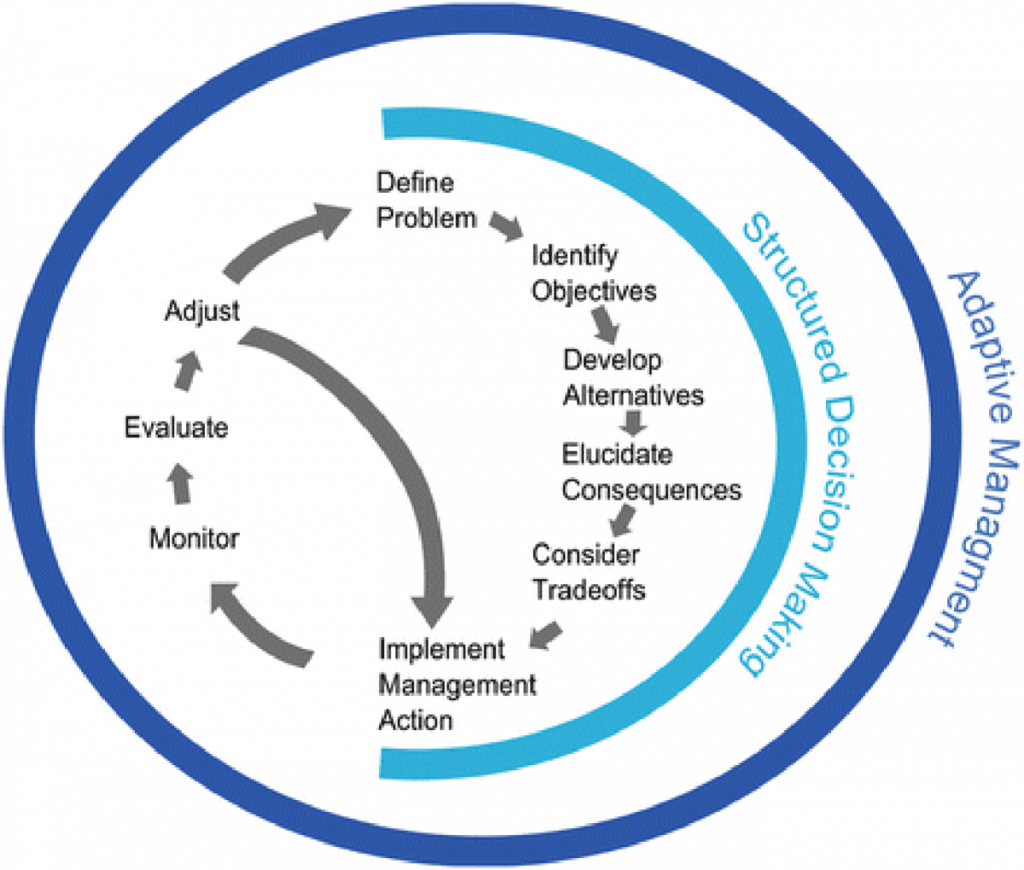

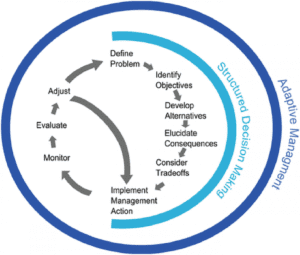

Adaptive management may be considered a “trial and error” approach to rangeland management. It starts with defining the problem, identifying objectives, and incorporating structured decision making (Figure 3). In addition, producers should consider alternative management approaches and evaluate consequences and tradeoffs of any management decision (Allen et al. 2017). All of this happens before you implement a management action. After a management action is made, the connection between structured decision making and adaptive management occurs by the additional steps of monitoring, evaluating and adjusting decisions. Although monitoring can be demanding, there are a few easy steps to take to set up record keeping, particularly as it concerns your natural resources. Evaluating what you monitor will then lead to adjustments in future management. It’s an ongoing cycle that is worth pursuing as producers think about increasing their operation’s flexibility and resiliency to perturbations.

References

- Allen CR et al. 2017 Adaptive Management of Rangeland Systems. In: Briske D. (eds) Rangeland Systems. Springer Series on Environmental Management. Springer, Cham.

- Derner, J.D., and Augustine, D.J. 2016. Adaptive Management for Drought on Rangelands. Rangelands 38(4): 211-215.